![[logo]](/images/SimplyGenius.png)

Simply Genius .NET

Software that makes you smile

Is the Ready Queue FIFO?

|

|

Publicly recommend on Google

|

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- The Long Answer

- Asynchronous Procedure Calls (APCs)

- Message Queue Messages

- The Short Answer

- The Proof

- Points of Interest

- Conclusion

- History

Introduction

This is a short article that answers the question: is the ready queue FIFO?

Here are three quick answers - all are benign:

- Beginner: No, it's non-deterministic

- Intermediate: Yes, but don't rely on it

- Advanced: Yes, but threads can be moved to the back of the queue while waiting

The rest of this article will explore the real answer with a small program as proof.

Background

There is little definitive information about the details of multi-threading on the web, and what little exists is spread across many sites and blogs. Indeed, there seems to be a lot of misleading, or just plain wrong information that propagates from one blog to another. My aim with this article is to provide a definitive answer to a specific question, and to also provide proof in the form of a small application that you can download and investigate yourself.

The Long Answer

When a thread blocks, for example when trying to acquire a lock that is already held by another thread, it waits in the kernel. The kernel keeps a queue of threads that are waiting for a particular lock, which is called the ready queue. The ready queue is implemented as a First-In-First-Out queue ( but don't rely on that! ).

So, you would expect that if two threads tried to acquire a contended lock, then the first one to ask for the lock would be the first one to acquire it. This, unfortunately, happens most of the time. I say 'unfortunately', because it is not consistent behaviour. This means that if you rely on the common behaviour, you will have introduced a bug that seems to occur randomly and infrequently. These are, of course, the hardest bugs to find and fix.

Waiting in Native Code

The native function that is used by the CLR to wait is CoWaitForMultipleHandles. On a Single Threaded Apartment (STA) thread, this function calls MsgWaitForMultipleObjectsEx, and on other threads, it calls WaitForMultipleObjectsEx. Both of these functions can return early due to an Asynchronous Procedure Call (APC). MsgWaitForMultipleObjectsEx can also return when a message is in the thread's message queue.

Asynchronous Procedure Calls (APCs)

The kernel often needs to run little sections of code, for example, when a file read or write completes. Rather than use a dedicated thread to run these, the kernel 'borrows' any thread that is waiting (in an alertable wait state), and just runs the APC on top of the existing stack of that thread. If this happens, the wait function returns WAIT_IO_COMPLETION and it is up to the thread to decide what to do - probably restart the wait with a suitably reduced timeout value.

Message Queue Messages

If MsgWaitForMultipleObjectsEx is called, it will return whenever a selected message is added to the thread's message queue. Messages are selected using the dwWakeMask parameter. When a selected message arrives, the wait returns and the thread has the opportunity to process the message. As above, it can then decide whether to restart the wait.

CoWaitForMultipleHandles wraps some of this boilerplate code and handles COM RPC calls. These must be handled to prevent deadlocks, for example, in the case when a thread calls into a COM server, which then calls back into the original thread. If the wait was not alertable, the second RPC would deadlock.

Waiting in Managed Code

The CLR has one single method that is called whenever a thread waits for any reason. This method always issues alertable waits using CoWaitForMultipleHandles, so it can pump COM messages and some other Windows messages. It also handles the common issues mentioned above, like calculating a new timeout if a wait returns early.

The Short Answer

So, the CLR always runs alertable waits. This means that during a call to say, Monitor.Enter, your thread can wake up, execute some unknown code, and then go back to waiting. All unbeknownst to your wait code.

This is the behaviour that breaks the FIFO nature of the ready queue. When a thread wakes up, it is removed from the queue. When it goes back to waiting, it is added at the end of the queue. So, another thread that blocked after our thread will be ahead when the resource becomes free.

The Proof

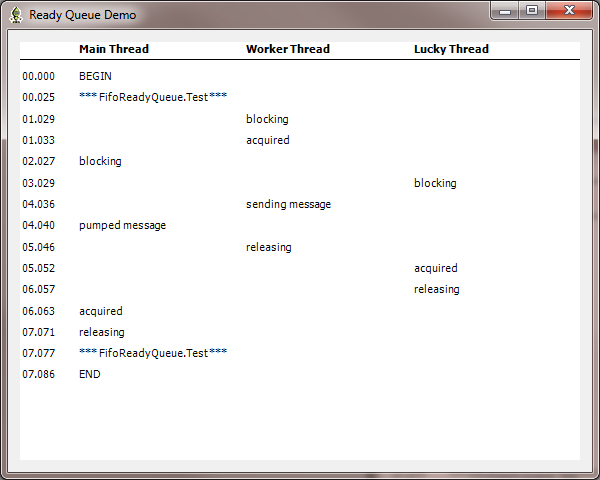

This section explains the demo application shown in the screenshot above. Each of the three threads attempts to obtain a lock on the same object. This is shown in the screenshot as the sequence:

- blocking

- acquired

- releasing

The code for each thread follows this pattern:

Form1.Add( "blocking" );

lock ( key )

{

Form1.Add( "acquired" );

Thread.Sleep( 1000 );

Form1.Add( "releasing" );

}

The worker thread acquires the lock first, then the main thread tries to acquire it (and blocks), then the lucky thread does the same. You can see that although the main thread enters the ready queue first, it is the lucky thread that acquires the lock when it becomes available.

The reason for this is that the worker thread sends a Windows message (in the WM_USER range) to the main thread while the main thread is blocked. The main thread is woken by the CLR wait routine to handle this message. This is shown by the "pumped message" entry while the main thread is blocked. The CLR then puts the main thread back in the ready queue, but at the end - behind the lucky thread. So the lucky thread is now the first entry in the ready queue, and so acquires the lock first when it becomes available.

W5 ( Which Was What Was Wanted )

Points of Interest

As I am blocking the UI thread ( not an example of best practice ), I needed a UI element that can be updated from any thread. So, I wrote ConcurrentList, which allows any thread to add an entry and the control updates the display immediately on that thread. This is possible because CreateGraphics is one of the five members of Control that are thread safe. This is not a production-quality solution, because ( most! ) Windows messages are not pumped, which means the UI doesn't respond to user input. However, it works for the purposes of this demonstration.

Conclusion

Well, I hope that's cleared up this question. The ready queue may be FIFO, but you can't rely on that because threads can be reordered while waiting in the queue.

I hope you enjoyed this article. Thanks.

History

- 2009 - 07 - 26 : v1.0

License

This article, along with any associated source code and files, is licensed under The Code Project Open License.

Contact

If you have any feedback, please feel free to contact me.